Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Until now, it has been difficult to accurately predict the efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A novel indicator, the lung immune prognostic index (LIPI), has shown relatively high prognostic value in patients with solid cancer. Therefore, this study aimed to further identify the association between LIPI and the survival of patients with NSCLC who receive immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

Methods:

Several electronic databases were searched for available publications up to April 23, 2023. Immunotherapy outcomes included overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Subgroup analysis based on the study design and comparison of the LIPI was conducted.

Results:

In this meta-analysis, 21 studies with 9,010 patients were included in this meta-analysis. The pooled results demonstrated that elevated LIPI was significantly associated with poor OS (HR = 2.50, 95% CI:2.09–2.99, p < 0.001) and PFS (HR = 1.77, 95% CI:1.64–1.91, p < 0.001). Subgroup analyses stratified by study design (retrospective vs. prospective) and comparison of LIPI (1 vs. 0, 2 vs. 0, 1–2 vs. 0, 2 vs. 1 vs. 0, 2 vs. 0–1 and 2 vs. 1) showed similar results.

Conclusion:

LIPI could serve as a novel and reliable prognostic factor in NSCLC treated with ICIs, and elevated LIPI predicts worse prognosis.

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the most common malignancy and leading cause of tumor-related deaths worldwide [1, 2]. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of all lung cancer cases [3]. Despite great advances in early screening, surgical techniques, and adjuvant therapies for NSCLC, the overall prognosis remains poor, representing a relatively high risk of recurrence and therapeutic resistance [4, 5]. In the last few years, immunotherapy has become an important treatment option for NSCLC, especially for patients with advanced-stage and metastatic NSCLC. Unfortunately, less than 20% of patients could benefit from immunotherapy [6].

In clinics, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), particularly anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1)/programmed death 1 (PD-1) antibodies, are widely used as first- or second-line treatments for metastatic/advanced NSCLC alone or in combination with chemotherapy. However, as mentioned above, the number of patients who benefit from ICIs is fairly limited [6]. Thus, accurate and effective indicators to predict the efficacy of ICIs are urgently needed to help select potential beneficiaries of ICIs. Overall, PD-L1 expression and tumor mutation burden (TMB) are the most commonly used biomarkers to select ICI-advantaged populations and predict prognosis. Nevertheless, the predictive effect of these two biomarkers on ICI efficacy is not satisfactory in clinical practice [7, 8]. Patients with high PD-L1 expression are more likely to experience better survival, but a subset of patients do not benefit from immunotherapy [9, 10]. Therefore, further exploration of effective predictive indicators for the prognosis of ICIs treated NSCLC is required.

Since the immune checkpoint pathway includes an important circulatory phase, changes in some parameters based on peripheral blood may be associated with the response to immunotherapy. Increasing evidence suggests that inflammatory responses play an essential role in the development and progression of cancers [11, 12]. The inflammatory process in the body is considered to be the immune resistance mechanism in cancer patients, which promotes the growth and spread of tumor cells and activates the carcinogenic signaling pathway [11, 12]. Some biomarkers, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (dNLR), and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) have been used to detect inflammatory status and predict prognosis in various cancers, including NSCLC [11–14]. The lung immune prognostic index (LIPI) is a novel indicator based on a dNLR >3 and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) > upper limit of normal range (ULN), which was first reported by Mezquita et al. [15]. Patients were divided into three groups based on the number of risk factors from the LIPI: low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk groups with 0, 1, and 2 risk factors, respectively. Previous studies have revealed that pretreatment LIPI play a role in predicting the therapeutic outcomes of ICIs in patients with solid cancers. However, whether it can predict the prognosis of ICIs ICI-treated NSCLC remains unclear.

Therefore, this meta-analysis aimed to further identify the association between LIPI and survival of NSCLC patients receiving ICIs, which might contribute to the selection of an advantaged population and improvement of the therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapy among NSCLC patients.

Materials and methods

The current meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 [16].

Literature search

The PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and CNKI databases were searched from inception to April 23, 2023. The following terms were used for the search: PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, ICIs, immune checkpoint inhibitor, lung, pulmonary, cancer, tumor, carcinoma, neoplasm, LIPI, lung immune prognostic index, survival, prognosis, and prognostic. The detailed search strategies were as follows: (PD-1 OR PD-L1 OR CTLA-4 OR ICIs OR immune checkpoint inhibitor) AND (lung OR pulmonary) AND (cancer OR tumor OR carcinoma OR neoplasm) AND (LIPI OR lung immune prognostic index) AND (survival OR prognosis OR prognostic). Free text and Medical Subject Headings terms were also applied. All the references cited in the included studies were reviewed.

Inclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were included:1) patients were pathologically diagnosed with primary NSCLC; 2) patients who received ICIs with or without other combined therapies such as chemotherapy; 3) LIPI score was assessed according to the dNLR values and LDH level before immunotherapy, and the association between LIPI and efficacy of immunotherapy was evaluated; 4) the overall survival (OS) and (or) progression-free survival (PFS) were defined as outcomes of immunotherapy; 5) hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for OS and PFS were directly reported in articles.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that met any of the following criteria were excluded:1) low-quality studies; 2) letters, editorials, reviews, case reports, or animal trials; and 3) studies with insufficient or duplicated data.

Data extraction

The following information was collected from the included studies: name of first author, publication year, country, study design (retrospective or prospective), sample size, TNM stage, pathological type, detailed drugs of ICIs, threshold and comparison of LIPI, endpoint, HR, and 95% CI.

Quality assessment

Owing to the nature of the included studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) score system was used to evaluate the quality of the included studies. As mentioned above, only high-quality studies with an NOS score ≥6 were included.

The literature search, selection, information collection, and quality assessment were conducted by two authors independently and any disagreement was resolved by team discussion.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 12.0. Heterogeneity between studies was evaluated using I2 statistics and Q test. If significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 > 50% and/or p < 0.1), the random-effects model was applied; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used. HRs and 95% CIs were combined to evaluate the association between the LIPI, OS, and PFS. Subgroup analysis based on study design (retrospective vs. prospective) and comparison of LIPI (1 vs. 0, 2 vs. 0, 1–2 vs. 0, 2 vs. 1 vs. 0, 2 vs. 0–1 and 2 vs. 1) were conducted. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to detect the sources of heterogeneity and assess the stability of the overall results. Furthermore, Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were conducted to detect publication bias, and significant publication bias was defined as p < 0.05 [17–19].

Results

Literature search and selection

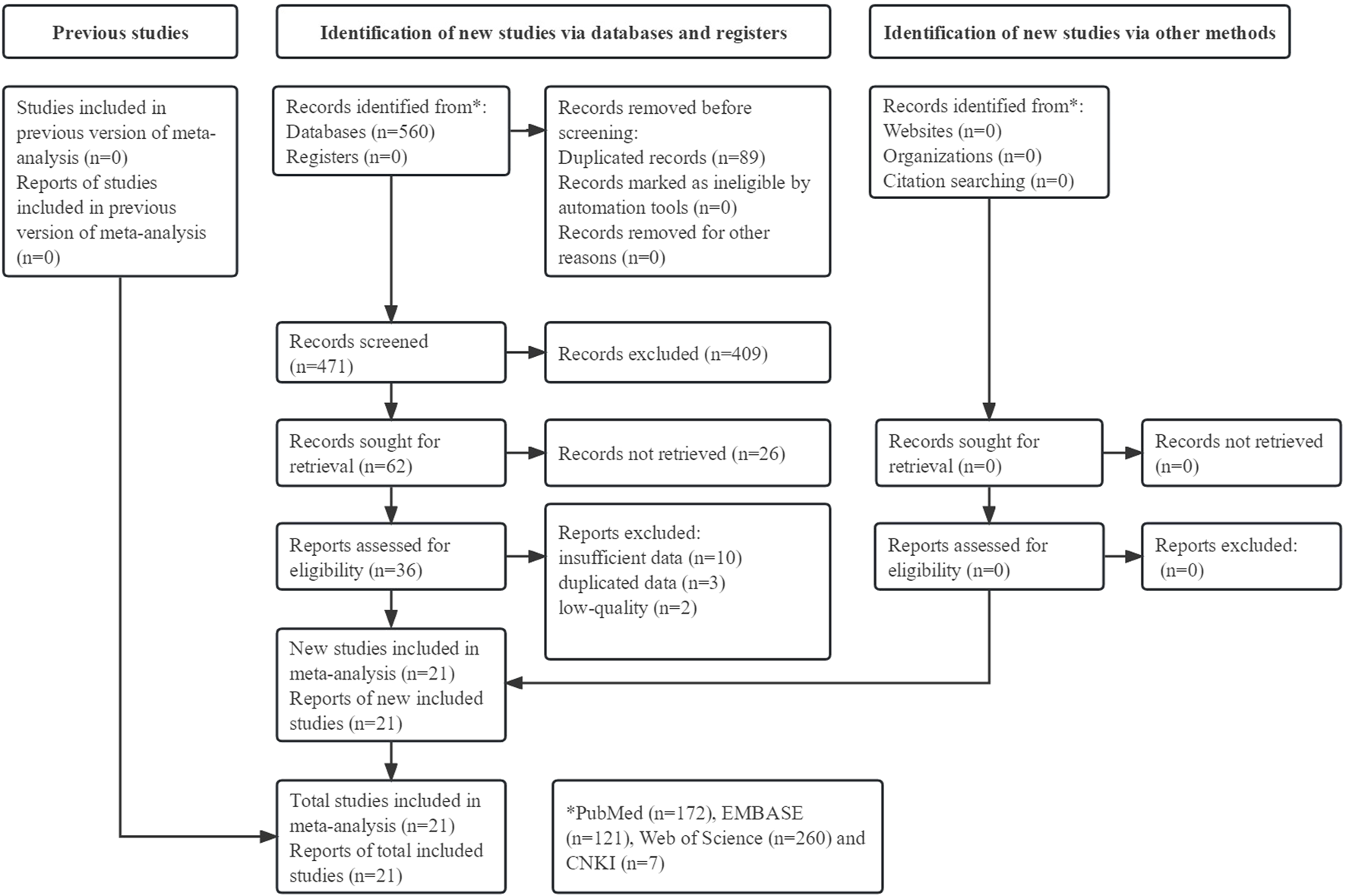

The detailed process is illustrated in Figure 1. Initially, 560 records were searched from four databases and a total of 21 studies were included [15, 20–39].

FIGURE 1

Prisma flow diagram of this meta-analysis.

Basic characteristics of included studies

A total of 9,010 participants were enrolled in 21 studies published between 2018 and 2023. Most of the included studies were retrospective and focused on patients with advanced NSCLC. The sample size ranged from 51 to 1,489, and all studies applied the same definition of LIPI risk grading: LIPI 0, dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; LIPI 1, dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; and LIPI 2, dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN. Specific data are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Author | Year | Country | Study design | Sample size | TNM stage | Pathological type | ICIs | Threshold and comparison of LIPI | Endpoint | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mezquita [15] | 2018 | France | R | 466 | IIIB-IV | Mixed | Nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and durvalumab-ipilimumab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1 and 0 vs. 2 | OS, PFS | 7 |

| Kazandjian [20] | 2019 | United States | P | 1,368 | IV | Mixed | NR | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 2 and 1 vs. 2 | OS, PFS | 8 |

| Ruiz-Bañobre [21] | 2019 | Spain | R | 188 | IIIB-IV | Mixed | Nivolumab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1 vs. 2 | OS, PFS | 8 |

| Sorich [22] | 2019 | Australia | P | 1,489 | Advanced | Mixed | Atezolizumab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1 and 0 vs. 2 | OS, PFS | 7 |

| Mazzaschi [23] | 2020 | Italy | P | 109 | IV | Mixed | NR | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1 vs. 2 | OS, PFS | 8 |

| Wang [24] | 2020 | China | R | 330 | IIIB-IV | Mixed | Nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, and other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0vs 1 and 0 vs. 2 | OS, PFS | 8 |

| Ali [25] | 2021 | China | R | 73 | IV | Mixed | Pembrolizumab, nivolumab, camrelizumab and atezolizumab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1–2 | OS, PFS | 6 |

| Galland [27] | 2021 | France | R | 231 | NR | Adenocarcinoma | PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1–2 | OS, PFS | 6 |

| Grosjean [28] | 2021 | Canada | R | 327 | I-IV | Mixed | Pembrolizumab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1–2 | OS | 6 |

| Hopkins [29] | 2021 | Australia | P | 1,148 | Advanced | Mixed | Atezolizumab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1 and 0 vs. 2 | OS, PFS | 6 |

| Mountzios [30] | 2021 | Greece | R | 672 | IV | Mixed | PD-L1 inhibitors | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1–2 | OS, PFS | 6 |

| Chen [26] | 2021 | China | R | 84 | IIIB-IV | Mixed | PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1–2 | OS, PFS | 6 |

| Chen [31] | 2022 | China | R | 85 | IV | Mixed | PD-1 inhibitors | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1–2 | OS, PFS | 6 |

| De Giglio [32] | 2022 | Italy | R | 182 | IV | Mixed | NR | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1–2 | OS | 6 |

| Holtzman [33] | 2022 | Israel | R | 423 | III-IV | Mixed | Pembrolizumab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1–2 | OS | 6 |

| Ortega-Franco [34] | 2022 | United Kingdom | R | 113 | III-IV | Mixed | Pembrolizumab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1 | OS, PFS | 6 |

| Tanaka [35] | 2022 | Japan | R | 237 | I-IV | Mixed | NR | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0–1 vs. 2 | OS, PFS | 6 |

| Zhou J [36] | 2022 | China | R | 51 | IIIB-IV | Mixed | PD-1 inhibitors | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1–2 | PFS | 6 |

| Zhou S [37] | 2022 | China | R | 53 | IV | Mixed | Pembrolizumab, nivolumab, sintilimab, camrelizumab, tislelizumab, and atezolizumab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0–1 vs. 2 | PFS | 6 |

| Zhou Y [38] | 2022 | China | R | 86 | I-IV | Mixed | Pembrolizumab, nivolumab and sindillimab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 1 and 0 vs. 2 | PFS | 7 |

| Huang [39] | 2023 | China | R | 147 | IIIB-IV | Mixed | Nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, treprizumab, carrelizumab, sintilimab and tislelizumab | 0: dNLR≤3 and LDH ≤ ULN; 1: dNLR >3 or LDH > ULN; 2: dNLR >3 and LDH > ULN; 0 vs. 2 and 1 vs. 2 | PFS | 7 |

Basic characteristics of included studies.

ICIs: immune checkpoint inhibitors; LIPI: lung immune prognostic index; NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; R: retrospective; P: prospective; NR: not reported; PD-1: programmed death-1; PD-L1: programmed cell death 1 ligand 1; dNLR: derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; ULN: upper limit of normal level; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; OS: overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival.

Association between LIPI and OS and PFS

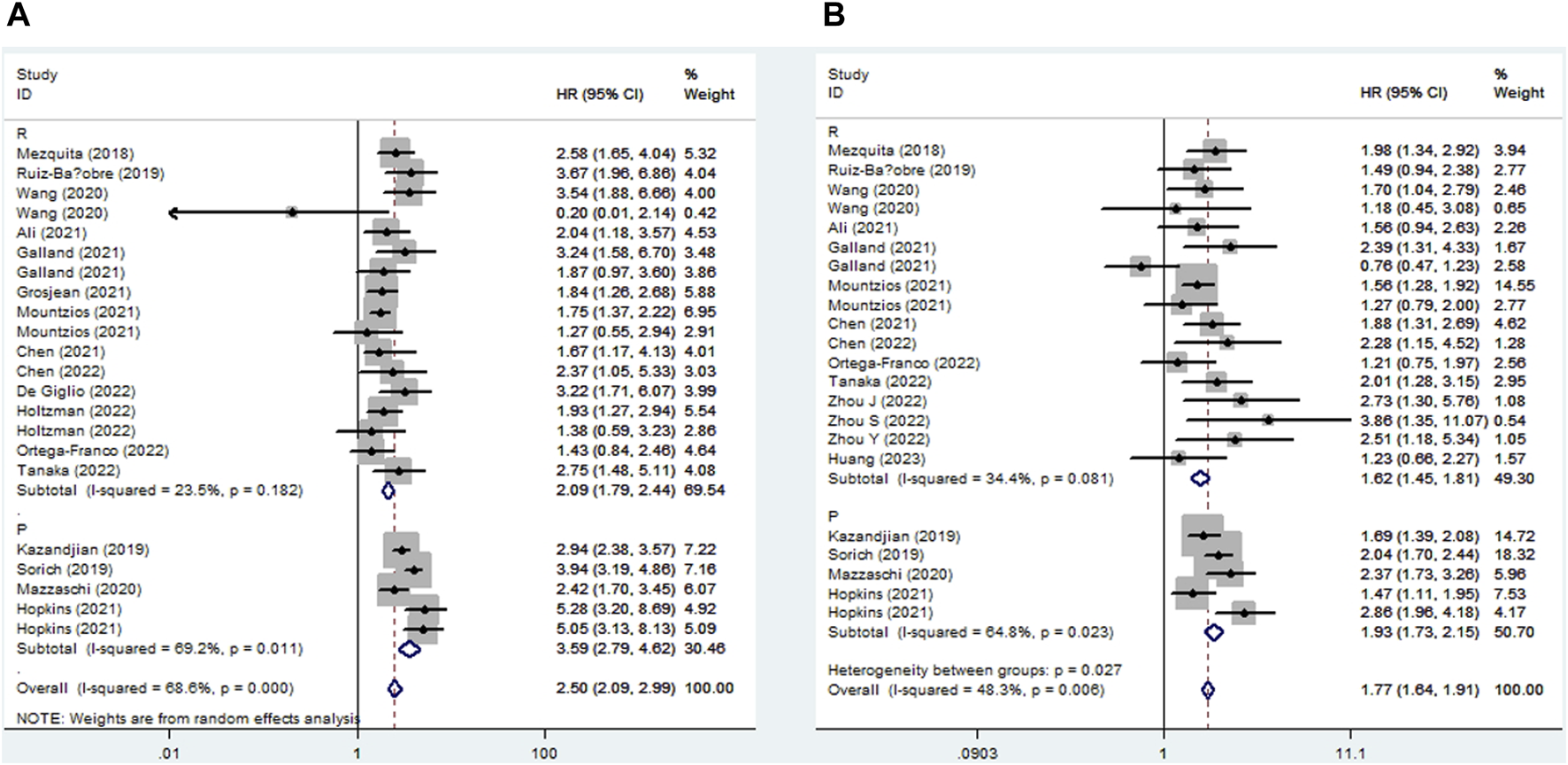

Seventeen studies explored the relationship between LIPI and OS in NSCLC patients receiving ICIs. The pooled results showed that elevated LIPI predicted poorer OS (HR = 2.50, 95% CI:2.09–2.99, p < 0.001; I2 = 68.6%, p < 0.001), and subgroup analysis based on the study design showed the same results (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2

Subgroup analysis based on study design for the association between LIPI and overall survival (A) and progression-free survival (B) of non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Eighteen studies identified a relationship between LIPI and PFS in immunotherapy-treated NSLC. The pooled results demonstrated that elevated LIPI was obviously associated with poor PFS (HR = 1.77, 95% CI:1.64–1.91, p < 0.001; I2 = 48.3%, p = 0.006), and subgroup analysis stratified by study design further verified the significant relationship between LIPI and PFS (Figure 2B).

Subgroup analysis for OS

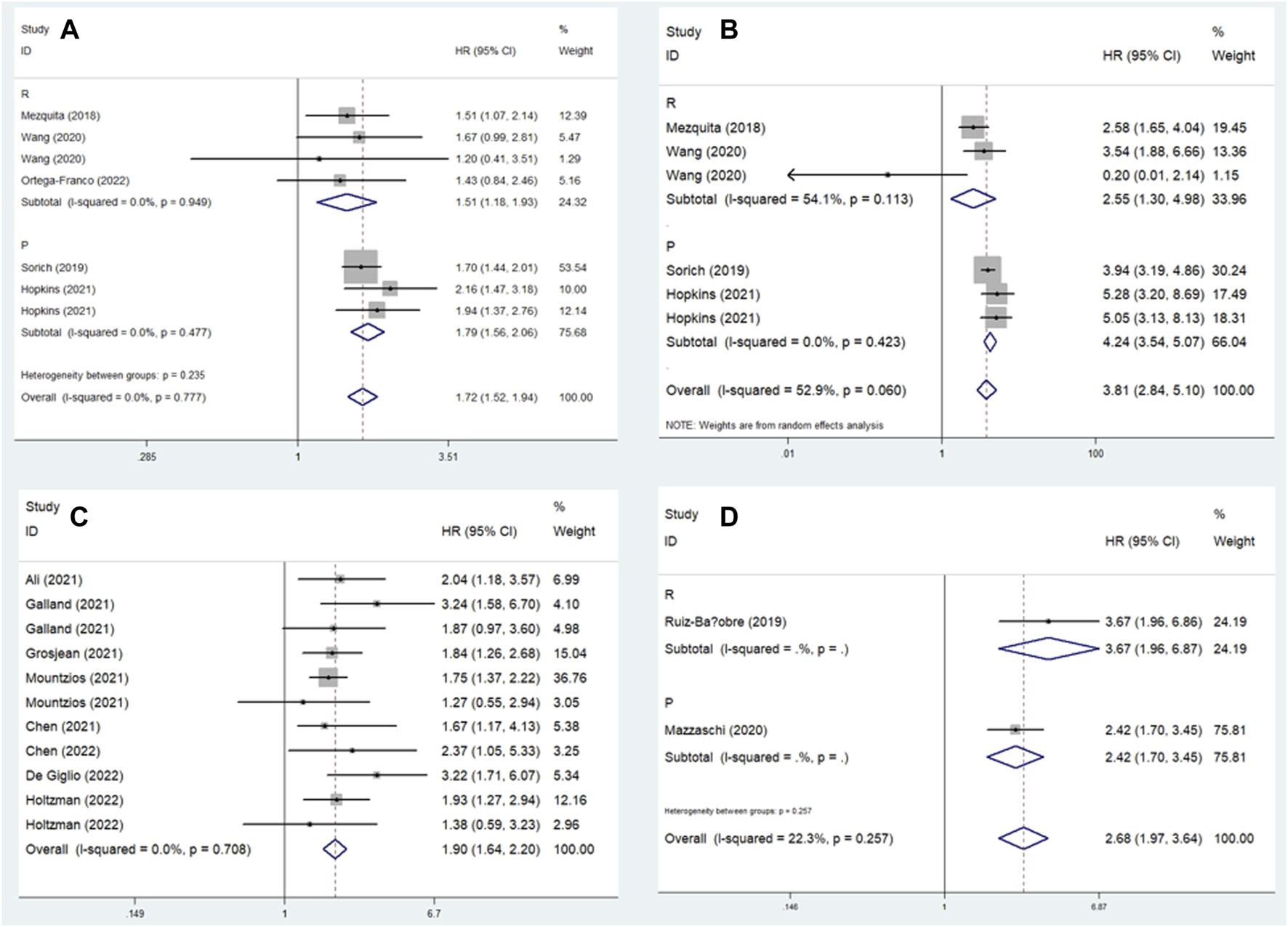

In this meta-analysis, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on a comparison of the LIPI and study design. The pooled results further demonstrated that elevated LIPI was significantly related to worse OS (LIPI 1 vs. 0: HR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.52–1.94, p < 0.001; LIPI 2 vs. 0: HR = 3.81, 95% CI: 2.84–5.10, p < 0.001; LIPI 1–2 vs. 0: HR = 1.90, 95% CI: 1.64–2.20, p < 0.001; LIPI 2 vs. 1 vs. 0: HR = 2.68, 95% CI: 1.97–3.64, p < 0.001; LIPI 2 vs. 0–1: HR = 2.75, 95% CI: 1.48–5.11, p < 0.001; LIPI 2 vs. 1: HR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.37–2.08, p < 0.001). In addition, a more specific subgroup analysis based on study design for the comparison of LIPI 1 vs. 0 (Figure 3A), LIPI 2 vs. 0 (Figure 3B), LIPI 1–2 vs. 0 (Figure 3C), and LIPI 2 vs. 1 vs. 0 (Figure 3D) further identified the above findings. Detailed results are presented in Table 2.

FIGURE 3

Subgroup analysis based on study design for the association between LIPI and overall survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. (A) LIPI 1 vs. 0; (B) LIPI 2 vs. 0; (C) LIPI 1–2 vs. 0; (D) LIPI 2 vs. 1 vs. 0.

TABLE 2

| No. of studies | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-Value | I2 (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||||||

| Overall | 17 | 2.50 | 2.09–2.99 | <0.001 | 68.6 | <0.001 |

| Retrospective | 13 | 2.09 | 1.79–2.44 | <0.001 | 23.5 | 0.182 |

| Prospective | 4 | 3.59 | 2.79–4.62 | <0.001 | 69.2 | 0.011 |

| LIPI 1 vs. 0 | 5 | 1.72 | 1.52–1.94 | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.777 |

| Retrospective | 3 | 1.51 | 1.18–1.93 | 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.949 |

| Prospective | 2 | 1.79 | 1.56–2.06 | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.477 |

| LIPI 2 vs. 0 | 4 | 3.81 | 2.84–5.10 | <0.001 | 52.9 | 0.423 |

| Retrospective | 2 | 2.55 | 1.30–4.98 | 0.006 | 54.1 | 0.113 |

| Prospective | 2 | 4.24 | 3.54–5.07 | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.423 |

| LIPI 1–2 vs. 0 | 8 | 1.90 | 1.64–2.20 | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.708 |

| Retrospective | 8 | 1.90 | 1.64–2.20 | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.708 |

| LIPI 2 vs. 1 vs. 0 | 2 | 2.68 | 1.97–3.64 | <0.001 | 22.3 | 0.257 |

| Retrospective | 1 | 3.67 | 1.96–6.87 | <0.001 | — | — |

| Prospective | 1 | 2.42 | 1.70–3.45 | <0.001 | — | — |

| LIPI 2 vs. 0–1 | 1 | 2.75 | 1.48–5.11 | <0.001 | — | — |

| Retrospective | 1 | 2.75 | 1.48–5.11 | <0.001 | — | — |

| LIPI 2 vs. 1 | 1 | 1.69 | 1.37–2.08 | <0.001 | — | — |

| Prospective | 1 | 1.69 | 1.37–2.08 | <0.001 | — | — |

| Progression-free survival | ||||||

| Overall | 18 | 1.77 | 1.64–1.91 | <0.001 | 48.3 | 0.006 |

| Retrospective | 14 | 1.62 | 1.45–1.81 | <0.001 | 34.4 | 0.081 |

| Prospective | 4 | 1.93 | 1.73–2.15 | <0.001 | 64.8 | 0.023 |

| LIPI 1 vs. 0 | 6 | 1.44 | 1.31–1.57 | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.979 |

| Retrospective | 4 | 1.35 | 1.13–1.61 | 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.927 |

| Prospective | 2 | 1.47 | 1.32–1.63 | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.982 |

| LIPI 2 vs. 0 | 6 | 1.91 | 1.69–2.16 | <0.001 | 41.0 | 0.105 |

| Retrospective | 4 | 1.75 | 1.36–2.24 | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.529 |

| Prospective | 2 | 1.97 | 1.71–2.27 | <0.001 | 75.0 | 0.018 |

| LIPI 1–2 vs. 0 | 6 | 1.60 | 1.26–2.04 | <0.001 | 55.3 | 0.028 |

| Retrospective | 6 | 1.60 | 1.26–2.04 | <0.001 | 55.3 | 0.028 |

| LIPI 2 vs. 1 vs. 0 | 2 | 1.94 | 1.24–3.05 | 0.004 | 61.8 | 0.106 |

| Retrospective | 1 | 1.49 | 0.94–2.37 | 0.092 | — | — |

| Prospective | 1 | 2.37 | 1.73–3.25 | <0.001 | — | — |

| LIPI 2 vs. 0–1 | 2 | 2.22 | 1.47–3.36 | <0.001 | 19.9 | 0.264 |

| Retrospective | 2 | 2.22 | 1.47–3.36 | <0.001 | 19.9 | 0.264 |

| LIPI 2 vs. 1 | 2 | 1.25 | 1.02–1.53 | 0.0 | 0.652 | |

| Retrospective | 1 | 1.09 | 0.58–2.04 | 0.788 | — | — |

| Prospective | 1 | 1.27 | 1.03–1.57 | 0.027 | — | — |

Results of meta-analysis.

LIPI: lung immune prognostic index.

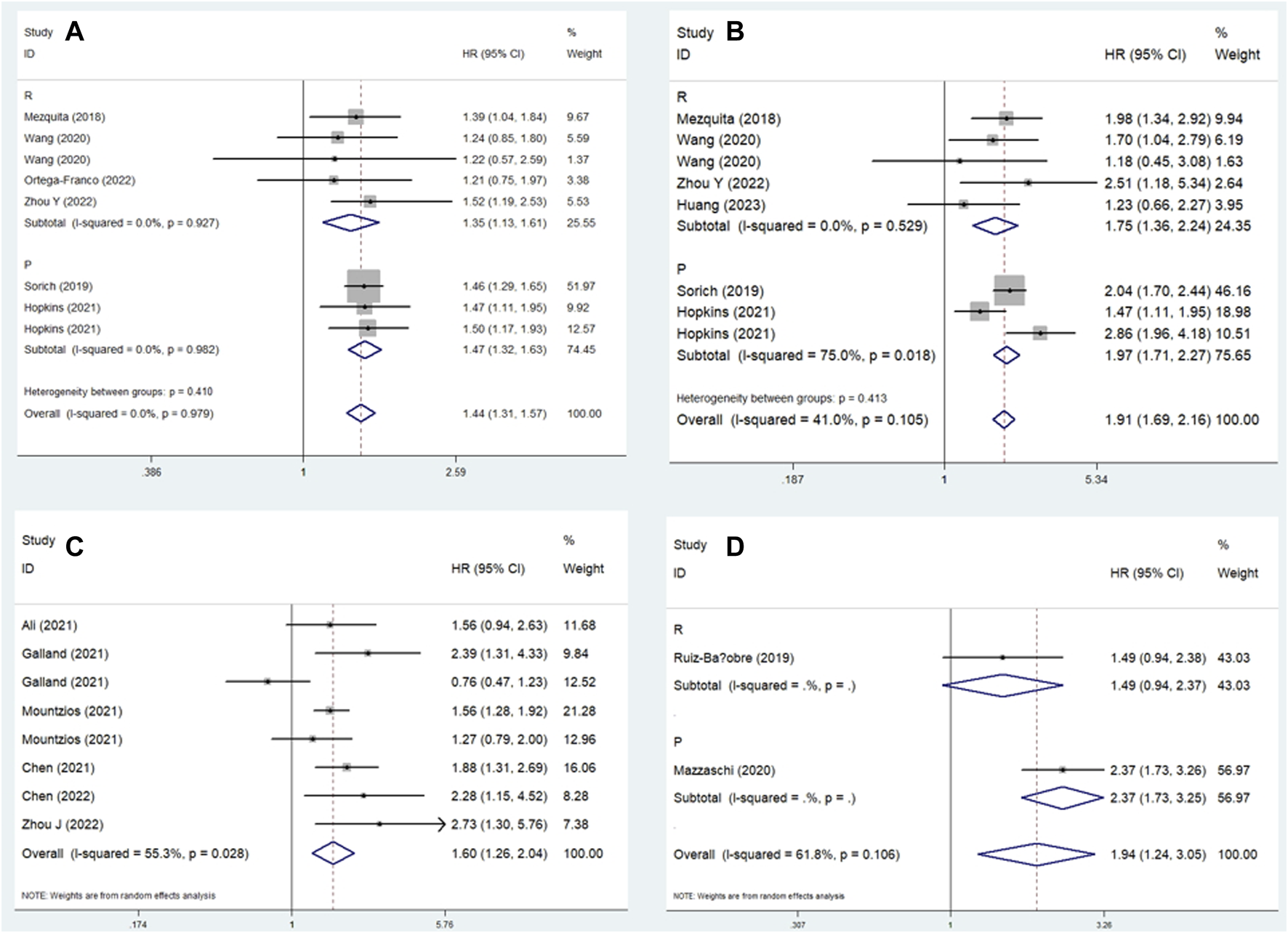

Subgroup analysis for PFS

Similarly, subgroup analysis for PFS based on the comparison of LIPI and the study design was performed. Pooled results revealed that elevated LIPI was obviously associated with poorer PFS (LIPI 1 vs. 0: HR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.31–1.57, p < 0.001; LIPI 2 vs. 0: HR = 1.91, 95% CI: 1.69–2.16, p < 0.001; LIPI 1–2 vs. 0: HR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.26–2.04, p < 0.001; LIPI 2 vs. 1 vs. 0: HR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.24–3.05, p = 0.004; LIPI 2 vs. 0–1: HR = 2.22, 95% CI: 1.47–3.36, p < 0.001; LIPI 2 vs. 1: HR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.02–1.53, p = 0.030). Furthermore, specific subgroup analysis based on study design for the comparison of LIPI 1 vs. 0 (Figure 4A), LIPI 2 vs. 0 (Figure 4B), LIPI 1–2 vs. 0 (Figure 4C), and LIPI 2 vs. 1 vs. 0 (Figure 4D) further confirmed the above findings. The detailed results are presented in Table 2.

FIGURE 4

Subgroup analysis based on study design for the association between LIPI and progression-free survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. (A) LIPI 1 vs. 0; (B) LIPI 2 vs. 0; (C) LIPI 1–2 vs. 0; (D) LIPI 2 vs. 1 vs. 0.

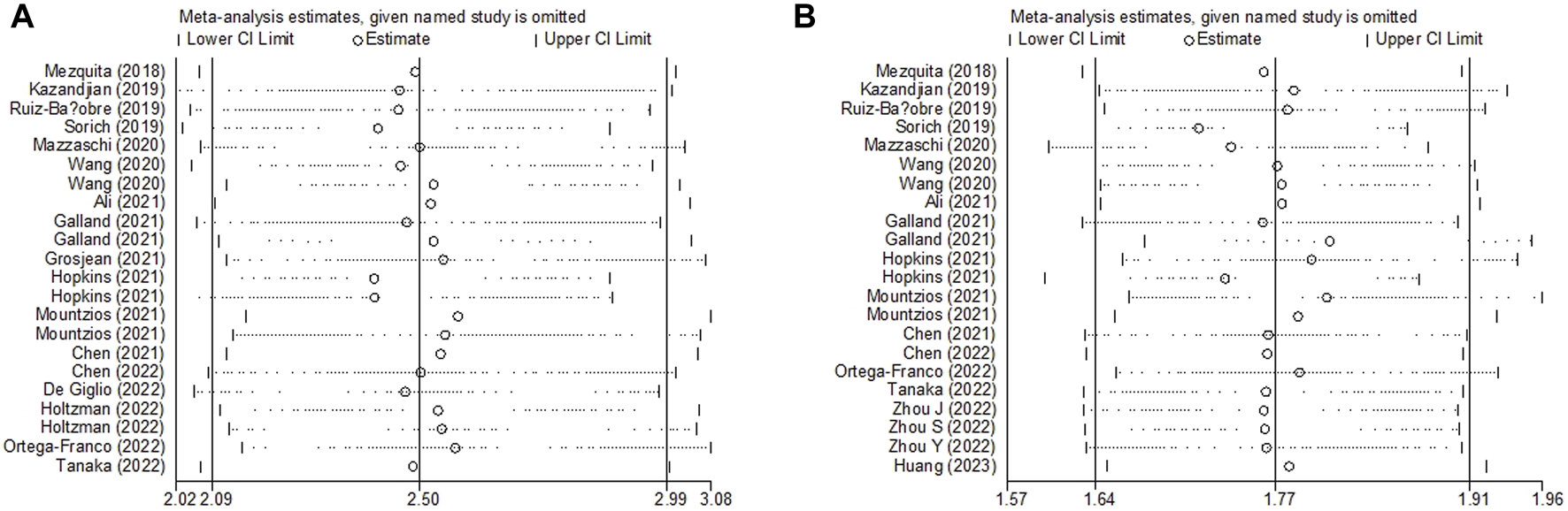

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis for the association between LIPI and OS and PFS was performed, which demonstrated that the pooled results of this meta-analysis were stable, and none of the included studies had an obvious impact on the relationship between LIPI and OS (Figure 5A) and PFS (Figure 5B) among immunotherapy-treated NSCLC patients.

FIGURE 5

Sensitivity analysis about the association between LIPI and overall survival (A) and progression-free survival (B) of non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors.

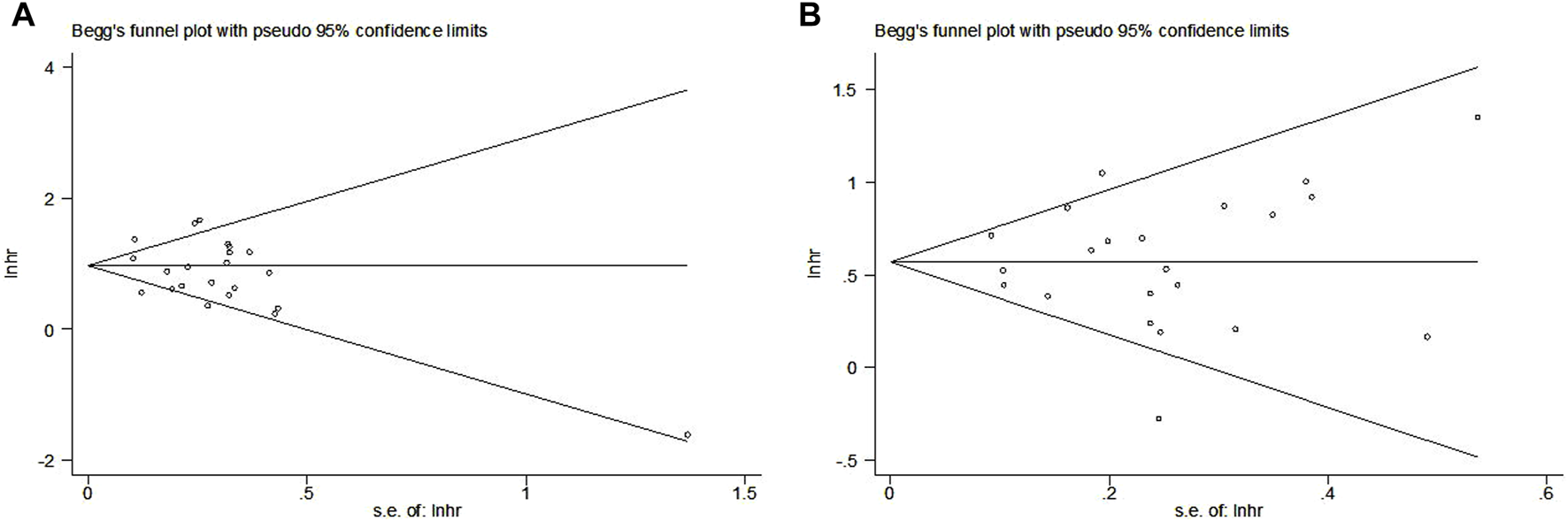

Publication bias

The Begg’s funnel plots for OS (Figure 6A) and PFS (Figure 6B) were both symmetrical, and the p-values of Egger’s test for OS and PFS were 0.208 and 0.992, respectively. Thus, no significant publication bias was observed in this meta-analysis.

FIGURE 6

Begg’s funnel plots for the association between LIPI and overall survival (A) and progression-free survival (B) of non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Discussion

This meta-analysis explored the predictive role of LIPI for the long-term survival of NSCLC patients who received ICIs based on current evidence, and the pooled results showed that LIPI was significantly associated with OS and PFS in this group of patients. Patients with elevated LIPIs were more likely to have a worse prognosis than patients with good LIPIs. Therefore, the LIPI could serve as a novel and reliable prognostic indicator in patients with NSCLC receiving ICIs.

The invasiveness of malignant tumors depends on the nature of tumor cells and their microenvironment. Previous studies have indicated that inflammation is a recognized feature of cancer, and inflammatory reactions play a crucial role in the process of carcinogenesis [40]. On the one hand, in malignant solid tumors, inflammatory stimulation leads to immune cell infiltration, angiogenesis, and fibroblast proliferation [41, 42]. In contrast, it is one of the mechanisms of immune tolerance, promoting tumor growth and dissemination, and activating oncogenic signaling pathways in cancer patients [43]. The dNLR was calculated using the neutrophil and lymphocyte counts. Neutrophils are key participants in tumor inflammation and immunity, and participate in tumor progression. Studies have found that neutrophils can produce vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which plays an important role in mediating tumor angiogenesis and is a powerful immunosuppressive factor of natural and adaptive anti-tumor immunity [44]. In addition, neutrophil-derived proteases can degrade cytokines and chemokines and reshape the extracellular matrix, and neutrophil elastase in tumor cells can overactivate the PI3K pathway, further accelerating uncontrolled tumor proliferation [45]. It has been reported that T cells producing interleukin (IL)-17 can release CXC chemokines to supplement neutrophils, and IL17a is involved in resistance to ICIs [46]. Therefore, higher dNLR levels may reflect negative inflammation and contribute to resistance to ICIs. Peripheral blood lymphocyte count is considered a predictive factor for the prognosis of various cancers [47]. Lymphocytes play an important role in tumor-related immunity, have potential anti-tumor immune functions to inhibit tumor development, participate in cytotoxic cell death and cytokine production, and inhibit tumor cell proliferation and metastasis through the immune response to cancer [48].

LDH is widely distributed in major human organs and catalyzes the conversion of lactate and pyruvate. It is an indicator of tumor burden, cell damage, and necrosis. Studies have shown that elevated LDH levels are an adverse prognostic factor for tumors [49, 50]. Elevated LDH levels are a product of enhanced tumor glycolysis and hypoxia-induced tumor necrosis [51]. On one hand, in tumors with increased glycolytic activity, both aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis under hypoxia can affect immune cell function due to glucose deficiency or tumor acidity [52]. Furthermore, hypoxia itself or the excessive expression of hypoxia-regulated factors in highly glycolytic tumors may affect antitumor immunity [53]. In addition, the main switch for hypoxia-induced angiogenesis, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), is activated by hypoxia and upregulates VEGF in tumors [54]. VEGF promotes tumor angiogenesis by inducing the proliferation and survival of endothelial cells, forming a large number of malformed and dysfunctional neovasculatures in the tumor [55]. These tumor blood vessels interfere with the active anticancer immune system and inhibit the therapeutic effect of ICI treatment. Therefore, LDH levels can affect the efficacy of ICIs.

Liu et al. included 12 studies with 4,883 solid cancer patients who received ICIs treatment and demonstrated that elevated pretreatment LIPI was significantly associated with worse OS (HR = 3.33, 95% CI:2.64–4.21, p < 0.001; HR = 1.71, 95%CI 1.43–2.04, p < 0.001) and PFS (HR = 2.73, 95% CI:2.00–3.73, p < 0.001; HR = 1.43, 95%CI 1.28–1.61, p < 0.001) [56]. However, only six studies explored the relationship between pretreatment LIPI and survival, and five studies were included in the pooled analysis [56]. In another meta-analysis by Xie et al., four studies involving 7,373 advanced NSCLC patients receiving ICIs, targeted therapy, or chemotherapy and their results revealed that intermediate and poor LIPI predicted worse OS (HR = 1.61, 95% CI:1.48–1.75, p < 0.01; HR = 2.74; 95% CI:2.26–3.33, p < 0.01) [57]. However, only three of the included studies identified the predictive role of pretreatment LIPI for OS in immunotherapy-treated NSCLC patients. Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis to determine the predictive value of LIPI for prognosis among patients with NSCLC receiving ICIs, and the pooled results indicated that LIPI could serve as a reliable prognostic factor in this group of patients.

This meta-analysis had several limitations that should be noted. First, all included studies were observational, and most of them were retrospectively conducted. Second, some of the included studies had relatively small sample sizes, which might have caused bias. Third, we were unable to conduct more subgroup analyses based on other parameters such as the pathological subtype, drugs of ICIs, and combinations of other therapies due to the lack of original data and sufficient information reported in the included studies.

Conclusion

Overall, LIPI could serve as a novel and reliable prognostic factor in NSCLC treated with ICIs, and intermediate LIPIs predict a worse prognosis. However, further high-quality studies are required to verify our findings.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

XX designed the study. YW, YL, and DZ performed the literature search and selection, collected the data, and wrote the paper. YY, LL, and JL performed statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.

TorreLASiegelRLJemalA. Lung cancer statistics. Adv Exp Med Biol (2016) 893:1–19. 10.1007/978-3-319-24223-1_1

2.

JenkinsRWalkerJ. 2022 cancer statistics: focus on lung cancer. Future Oncol (London, England) (2023) 1–11. 10.2217/fon-2022-1214

3.

SiegelRLMillerKDFuchsHEJemalA. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA: a Cancer J clinicians (2021) 71(1):7–33. 10.3322/caac.21654

4.

JuWZhengRZhangSZengHSunKWangSet alCancer statistics in Chinese older people, 2022: current burden, time trends, and comparisons with the US, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Sci China Life Sci (2022) 66:1079–91. 10.1007/s11427-022-2218-x

5.

SiegelRLMillerKDWagleNSJemalA. Cancer statistics. CA: a Cancer J clinicians (2023) 73(1):17–30. 10.3322/caac.21332

6.

GaronEBRizviNAHuiRLeighlNBalmanoukianASEderJPet alPembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med (2015) 372(21):2018–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824

7.

AdamTBeckerTMChuaWBrayVRobertsTL. The multiple potential biomarkers for predicting immunotherapy response-finding the needle in the haystack. Cancers (2021) 13(2):277. 10.3390/cancers13020277

8.

DongAZhaoYLiZHuH. PD-L1 versus tumor mutation burden: which is the better immunotherapy biomarker in advanced non-small cell lung cancer?J Gene Med (2021) 23(2):e3294. 10.1002/jgm.3294

9.

HerbstRSBaasPKimDWFelipEPérez-GraciaJLHanJYet alPembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) (2016) 387(10027):1540–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7

10.

ReckMRodríguez-AbreuDRobinsonAGHuiRCsősziTFülöpAet alPembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med (2016) 375(19):1823–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774

11.

WangYHuXXuWWangHHuangYCheG. Prognostic value of a novel scoring system using inflammatory response biomarkers in non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. Thorac Cancer (2019) 10(6):1402–11. 10.1111/1759-7714.13085

12.

TianLWangYTianJSongWLiLCheG. Prognostic value and genome signature of m6A/m5C regulated genes in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Mol Sci (2023) 24(7):6520. 10.3390/ijms24076520

13.

YangTHaoLYangXLuoCWangGLinCCet alPrognostic value of derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (dNLR) in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open (2021) 11(9):e049123. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049123

14.

PlatiniHFerdinandEKoharKPrayogoSAAmirahSKomariahMet alNeutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic markers for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with immunotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) (2022) 58(8):1069. 10.3390/medicina58081069

15.

MezquitaLAuclinEFerraraRCharrierMRemonJPlanchardDet alAssociation of the lung immune prognostic index with immune checkpoint inhibitor outcomes in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol (2018) 4(3):351–7. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4771

16.

PageMJMcKenzieJEBossuytPMBoutronIHoffmannTCMulrowCDet alThe PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed) (2021) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

17.

BeggCBMazumdarM. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics (1994) 50(4):1088–101. 10.2307/2533446

18.

EggerMDavey SmithGSchneiderMMinderC. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed) (1997) 315(7109):629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

19.

ZengXYeLLuoMZengDChenY. Prognostic value of pretreatment systemic immune-inflammation index in Chinese esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients receiving radical radiotherapy: a meta-analysis. Medicine (2023) 102(25):e34117. 10.1097/MD.0000000000034117

20.

KazandjianDGongYKeeganPPazdurRBlumenthalGM. Prognostic value of the lung immune prognostic index for patients treated for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol (2019) 5(10):1481–5. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1747

21.

Ruiz-BanobreJAreses-ManriqueMCMosquera-MartinezJCortegoAAfonso-AfonsoFJde Dios-AlvarezNet alEvaluation of the lung immune prognostic index in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients under nivolumab monotherapy. Translational Lung Cancer Res (2019) 8(6):1078–85. 10.21037/tlcr.2019.11.07

22.

SorichMJRowlandAKarapetisCSHopkinsAM. Evaluation of the lung immune prognostic index for prediction of survival and response in patients treated with atezolizumab for non-small cell lung cancer: pooled analysis of clinical trials. J Thorac Oncol : official Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer (2019) 15. 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.04.006

23.

MazzaschiGMinariRZeccaACavazzoniAFerriVMoriCet alSoluble PD-L1 and circulating cd8+pd-1+ and NK cells enclose a prognostic and predictive immune effector score in immunotherapy treated NSCLC patients. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) (2020) 148:1–11. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.07.028

24.

WangWHuangZYuZZhuangWZhengWCaiZet alPrognostic value of the lung immune prognostic index may differ in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy or combined with chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol (2020) 10:572853. 10.3389/fonc.2020.572853

25.

AliWASHuiPMaYWuYZhangYChenYet alDeterminants of survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Ann translational Med (2021) 9(22):1639. 10.21037/atm-21-1702

26.

ChenP. Clinical study on prognostic factors of immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Taiyuan, China: Shanxi Medical University (2021). Master.

27.

GallandLLe PageALLecuelleJBibeauFOulkhouirYDerangereVet alPrognostic value of Thyroid Transcription Factor-1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma in patients treated with anti PD-1/PD-L1. Oncoimmunology (2021) 10(1):1957603. 10.1080/2162402X.2021.1957603

28.

GrosjeanHAIDolterSMeyersDEDingPQStukalinIGoutamSet alEffectiveness and safety of first-line pembrolizumab in older adults with PD-L1 positive non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective cohort study of the Alberta immunotherapy database. Curr Oncol (2021) 28(5):4213–22. 10.3390/curroncol28050357

29.

HopkinsAMKichenadasseGAbuhelwaAYMcKinnonRARowlandASorichMJ. Value of the lung immune prognostic index in patients with non-small cell lung cancer initiating first-line atezolizumab combination therapy: subgroup analysis of the impower150 trial. Cancers (2021) 13(5):1176–9. 10.3390/cancers13051176

30.

MountziosGSamantasESenghasKZervasEKrisamJSamitasKet alAssociation of the advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) with immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO open (2021) 6(5):100254. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100254

31.

ChenJWeiSZhaoTWangYZhangX. Clinical significance of serum biomarkers in stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 inhibitors: LIPI score, NLR, dNLR, LMR, and PAB. Dis markers (2022) 2022:7137357. 10.1155/2022/7137357

32.

De GiglioATassinariEZappiADi FedericoALenziBSperandiFet alThe palliative prognostic (PaP) score without clinical evaluation predicts early mortality among advanced NSCLC patients treated with immunotherapy. Cancers (2022) 14(5845):5845. 10.3390/cancers14235845

33.

HoltzmanLMoskovitzMUrbanDNechushtanHKerenSReinhornDet aldNLR-based score predicting overall survival benefit for the addition of platinum-based chemotherapy to pembrolizumab in advanced NSCLC with PD-L1 tumor proportion score ≥50. Clin Lung Cancer (2022) 23(2):122–34. 10.1016/j.cllc.2021.12.006

34.

Ortega-FrancoAHodgsonCRajaHCarterMLindsayCHughesSet alReal-world data on pembrolizumab for pretreated non-small-cell lung cancer: clinical outcome and relevance of the lung immune prognostic index. Targeted Oncol (2022) 17(4):453–65. 10.1007/s11523-022-00889-8

35.

TanakaSUchinoJYokoiTKijimaTGotoYSugaYet alPrognostic nutritional index and lung immune prognostic index as prognostic predictors for combination therapies of immune checkpoint inhibitors and cytotoxic anticancer chemotherapy for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Diagnostics (2022) 12(2):423. 10.3390/diagnostics12020423

36.

ZhouJBaoMGaoGCaiYWuLLeiLet alIncreased blood-based intratumor heterogeneity (bITH) is associated with unfavorable outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitors plus chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Med (2022) 20(256):256. 10.1186/s12916-022-02444-8

37.

ZhouSRenFMengX. Efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in EGFR mutation-positive patients with NSCLC and brain metastases who have failed EGFR-TKI therapy. Front Immunol (2022) 13:955944. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.955944

38.

ZhouYWuLXuTMaCSongLZhangJ. Predictive value of lung immune prognostic index scoring system for patients treated with immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin J Med Offic (2022) 50(03):237–41. 10.16680/j.1671-3826.2022.03.05

39.

HuangJPuHHeJTangX. Prognostic value of the lung immune prognostic index for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients: a Chinese cohort study. Int J Gen Med (2023) 16:881–93. 10.2147/IJGM.S393263

40.

ShahSCItzkowitzSH. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: mechanisms and management. Gastroenterology (2022) 162(3):715–30.e3. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.035

41.

KolbM. Inflammation and dysregulated fibroblast proliferation--new mechanisms?Sarcoidosis, vasculitis, diffuse Lung Dis : official J WASOG (2013) 30(Suppl. 1):21–6.

42.

YuKLiDXuFGuoHFengFDingYet alIdo1 as a new immune biomarker for diabetic nephropathy and its correlation with immune cell infiltration. Int immunopharmacology (2021) 94:107446. 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107446

43.

AiLXuAXuJ. Roles of PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: signaling, cancer, and beyond. Adv Exp Med Biol (2020) 1248:33–59. 10.1007/978-981-15-3266-5_3

44.

MizunoRKawadaKItataniYOgawaRKiyasuYSakaiY. The role of tumor-associated neutrophils in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20(3):529. 10.3390/ijms20030529

45.

YangRZhongLYangXQJiangKLLiLSongHet alNeutrophil elastase enhances the proliferation and decreases apoptosis of leukemia cells via activation of PI3K/Akt signaling. Mol Med Rep (2016) 13(5):4175–82. 10.3892/mmr.2016.5051

46.

LiuCLiuRWangBLianJYaoYSunHet alBlocking IL-17A enhances tumor response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in microsatellite stable colorectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer (2021) 9(1):e001895. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001895

47.

HuangHLiuQZhuLZhangYLuXWuYet alPrognostic value of preoperative systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with cervical cancer. Scientific Rep (2019) 9(1):3284. 10.1038/s41598-019-39150-0

48.

TakadaKKashiwagiSAsanoYGotoWMorisakiTShibutaniMet alDifferences in tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte density and prognostic factors for breast cancer by patient age. World J Surg Oncol (2022) 20(1):38. 10.1186/s12957-022-02513-5

49.

ComandatoreAFranczakMSmolenskiRTMorelliLPetersGJGiovannettiE. Lactate Dehydrogenase and its clinical significance in pancreatic and thoracic cancers. Semin Cancer Biol (2022) 86(Pt 2):93–100. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.09.001

50.

DangCDengYHQinRY. Prognostic value of ALP and LDH in periampullary carcinoma patients undergoing surgery. Curr Med Sci (2022) 42(1):150–8. 10.1007/s11596-021-2452-9

51.

YeYChenMChenXXiaoJLiaoLLinF. Clinical significance and prognostic value of lactate dehydrogenase expression in cervical cancer. Genet Test Mol biomarkers (2022) 26(3):107–17. 10.1089/gtmb.2021.0006

52.

ParedesFWilliamsHCSan MartinA. Metabolic adaptation in hypoxia and cancer. Cancer Lett (2021) 502:133–42. 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.12.020

53.

ShaoXHuaSFengTOcanseyDKWYinL. Hypoxia-regulated tumor-derived exosomes and tumor progression: a focus on immune evasion. Int J Mol Sci (2022) 23(19):11789. 10.3390/ijms231911789

54.

KorbeckiJSimińskaDGąssowska-DobrowolskaMListosJGutowskaIChlubekDet alChronic and cycling hypoxia: drivers of cancer chronic inflammation through HIF-1 and NF-κB activation: a review of the molecular mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22(19):10701. 10.3390/ijms221910701

55.

MelincoviciCSBoşcaABŞuşmanSMărgineanMMihuCIstrateMet alVascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) - key factor in normal and pathological angiogenesis. Rom J Morphol Embryol = Revue roumaine de morphologie embryologie (2018) 59(2):455–67.

56.

LiuHYangXLYangXYDongZRChenZQHongJGet alThe prediction potential of the pretreatment lung immune prognostic index for the therapeutic outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with solid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol (2021) 11:691002. 10.3389/fonc.2021.691002

57.

XieJZangYLiuMPengLZhangH. The lung immune prognostic index may predict the efficacy of different treatments in patients with advanced NSCLC: a meta-analysis. Oncol Res Treat (2021) 44(4):164–75. 10.1159/000514443

Summary

Keywords

lung immune prognostic index, non-small cell lung cancer, immune checkpoint inhibitor, prognosis, meta-analysis

Citation

Wang Y, Lei Y, Zheng D, Yang Y, Luo L, Li J and Xie X (2024) Prognostic value of lung immune prognostic index in non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 30:1611773. doi: 10.3389/pore.2024.1611773

Received

21 March 2024

Accepted

11 June 2024

Published

20 June 2024

Volume

30 - 2024

Edited by

Nora Bittner, National Koranyi Institute of TB and Pulmonology, Hungary

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Wang, Lei, Zheng, Yang, Luo, Li and Xie.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoyang Xie, 13990559066@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.